The Typestate Pattern in C# - Redesigning PactNet

The typestate pattern uses the static type system of a language to move potential runtime errors to compile time errors instead. This article discusses the redesign of PactNet v4.0.0 to use that pattern to make code which would create invalid conditions impossible to compile instead of erroring at runtime.

Pact creates a contract between a consumer and a provider which can be verified during Continuous Integration to ensure that both components are compatible before they’re deployed to an environment. The consumer creates expectations which are exported in a format defined by the Pact Specification, then the file is later used to automate requests against the provider and verify the results are compatible.

A Simple Fluent Builder Pattern

Prior to PactNet v4, a provider test was typically built up using a fluent builder, which is a familiar pattern where a series of method calls establish the state, and each method returns the builder so that you can chain them all together.

The example from the documentation for provider tests looks like this (slightly trimmed for brevity):

const string serviceUri = "http://localhost:9222";

using (WebApp.Start<TestStartup>(serviceUri))

{

IPactVerifier pactVerifier = new PactVerifier();

var pactUriOptions = new PactUriOptions()

.SetBasicAuthentication("someuser", "somepassword") // you can specify basic auth details

// or

.SetBearerAuthentication("sometoken"); // Or a bearer token

pactVerifier

.ProviderState($"{serviceUri}/provider-states")

.ServiceProvider("Something API", serviceUri)

.HonoursPactWith("Consumer")

// use a file on disk

.PactUri("..\\..\\..\\Consumer.Tests\\pacts\\consumer-something_api.json")

// or grab a file from a web host

.PactUri("http://broker.example.org/pacts/provider/Something%20Api/consumer/Consumer/latest", pactUriOptions)

// or if you're using the Pact Broker

.PactBroker("http://broker.example.org", pactUriOptions)

.Verify();

}

On the face of this the API appears quite friendly, however this is only really the case if you follow the convention defined above and follow all those “and/or” instructions. In reality, the interface is defined something like this (again trimmed for brevity):

public interface IPactVerifier

{

IPactVerifier ProviderState(string providerStateSetupUri);

IPactVerifier ServiceProvider(string providerName, string baseUri);

IPactVerifier HonoursPactWith(string consumerName);

IPactVerifier PactUri(string fileUri, PactUriOptions options = null);

IPactVerifier PactBroker(string brokerBaseUri, PactUriOptions uriOptions = null);

void Verify();

}

The problem with this approach is that you can potentially create invalid or nonsensical states:

- You could define both a

PactUriandPactBrokersource and then it’s unclear what would happen. Does it use both? (spoiler: it doesn’t) - You could omit the provider or consumer name, or define them multiple times

- You could specify both HTTP and Bearer auth on

PactUriOptions - You could provide

PactUriOptionswhen using a local file path, which makes no sense - …and many more!

To catch these problems at runtime and try to enforce some kind of order and correctness, the implementation has to have

lots of runtime checks to make sure you didn’t create an invalid state. The Verify implementation has to have these checks:

public void Verify()

{

if (ProviderName == null)

{

throw new InvalidOperationException(

"providerName has not been set, please supply a service providerName using the ServiceProvider method.");

}

if (ServiceBaseUri == null)

{

throw new InvalidOperationException(

"baseUri has not been set, please supply a service baseUri using the ServiceProvider method.");

}

if (IsNullOrEmpty(PactFileUri) && IsNullOrEmpty(BrokerBaseUri))

{

throw new InvalidOperationException(

"PactFileUri or BrokerBaseUri has not been set, please supply a uri using the PactUri or PactBroker method.");

}

if (!IsNullOrEmpty(PactFileUri) && !IsNullOrEmpty(BrokerBaseUri))

{

throw new InvalidOperationException(

"PactFileUri and BrokerBaseUri have both been set, please use either the PactUri or PactBroker method, not both.");

}

// remainder omitted

}

This is a potentially frustrating development experience because the code compiles fine but then blows up at runtime.

The Typestate Pattern

For PactNet v4, I rewrote these APIs to use the typestate pattern so that:

- invalid states can’t be expressed, and the error is moved to compile-time if you attempt it

- IDE autocomplete guides you into the pit of success

- we can support different Pact Specification versions whilst still keeping compile-time correctness1

The new API is similar, but the interesting part is in how the design achieves the above advantages:

IPactVerifier pactVerifier = new PactVerifier();

pactVerifier

.ServiceProvider("Event API", new Uri("http://localhost:5000"))

.HonoursPactWith("Event API Consumer")

.FromPactFile(new FileInfo("/path/to/pact.json"))

.WithProviderStateUrl(new Uri("http://localhost:5000/provider-states"))

.Verify();

Defining the Provider and Consumer

We use the strong .Net type system to ensure that the verifier must be defined through a series of state machine transitions

(“typestates”) which must always be valid. The key is that the IPactVerifier interface for the starting state looks like this:

public interface IPactVerifier

{

IPactVerifierProvider ServiceProvider(string providerName, Uri pactUri);

}

public interface IPactVerifierProvider

{

IPactVerifierConsumer HonoursPactWith(string consumerName);

}

This means that a new pact verifier can only perform one action (defining the provider), and that one action

is guaranteed at compile time to be valid. The return type is the next valid state, an IPactVerifierProvider, in

which only one method is possible again (defining the consumer) and it’s guaranteed to be valid. At each stage you’ll

also get IDE autocomplete which shows you only valid states that you can move to from your current state.

Defining the Pact File Source

The next state is interesting because the state machine branches:

public interface IPactVerifierConsumer

{

IPactVerifierPair FromPactFile(FileInfo pactFile);

IPactVerifierPair FromPactUri(Uri pactUri);

IPactVerifierPair FromPactBroker(Uri brokerBaseUri, Action<IPactBrokerOptions> configure);

}

This state allows you to pick one of three different pact file sources, but the important thing is that you can only pick one. After you’ve chosen you move to the next state, so it’s no longer possible to define both a file source and a Pact Broker source.

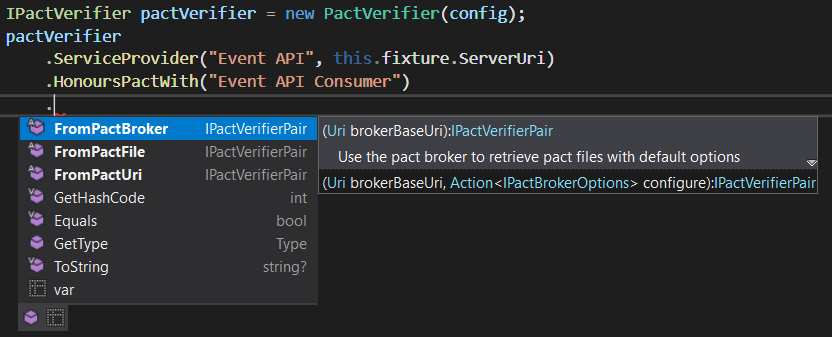

Again, auto-complete ensures you can only get valid options suggested:

Verifying the Pact

For completeness, the final state simply allows you to define some generic options such as log level before triggering the verification.

public interface IPactVerifierPair

{

IPactVerifierPair WithProviderStateUrl(Uri providerStateUri);

IPactVerifierPair WithFilter(string description = null, string providerState = null);

IPactVerifierPair WithLogLevel(PactLogLevel level);

void Verify();

}

Notice that the Verify method has a void return type - once you’ve triggered verification you are now in the final

state and can’t go back again.

One key strength of this approach is that from any of the intermediate typestates it’s impossible to call the final Verify

operation, and so the runtime checks are no longer necessary - if it compiles then it shouldn’t blow up at runtime. This

creates a much better experience for the developer.

Shortcomings of Typestates in C# vs. Rust

The typestate pattern was made popular in Rust, which has a very strong ownership model that C# lacks. In Rust the first two typestates would look something like:

impl PactVerifier {

pub fn service_provider(self, provider: &str) -> PactVerifierProvider {

// ...

}

}

impl PactVerifierProvider {

pub fn honours_pact_with(self, consumer: &str) -> PactVerifierConsumer {

// ...

}

}

For those unfamiliar with Rust, the use of self (instead of taking a reference such as &self or &mut self) transfers

ownership of the calling object into the function, and then it can never be used again because the function returns a

different object. You can’t do this:

let verifier = PactVerifier::new();

verifier.service_provider("provider");

// this won't compile - verifier ownership was transferred so you can't use the object again

verifier.service_provider("another provider");

In C#, however, there’s no way to prevent the user storing the intermediate states and trying to use them again:

var verifier = new PactVerifier();

var foo = verifier.ServiceProvider("foo");

var bar = verifier.ServiceProvider("bar");

Assert.Equal(verifier.Provider, "bar"); // foo has been overwritten

In reality you can attempt to combat this by making each state completely immutable so that an entire new state is returned by each method call instead of mutating a common state, but this may not always be possible and may be inefficient with large states or when used frequently.

Conclusion

Overall I think the typestate pattern provides a really nice developer experience, even if the tools available in C# (and other languages other than Rust) mean that it can never quite be perfect. The benefits are certainly worth it though and the overall result is much better than the ubiquitous fluent builder pattern.

I think one important design point is not to overuse the pattern. In the final IPactVerifierPair typestate above, it is

still technically possible to define some of the options more than once, where the final invocation wins:

IPactVerifier pactVerifier = new PactVerifier();

pactVerifier

.ServiceProvider("Event API", new Uri("http://localhost:5000"))

.HonoursPactWith("Event API Consumer")

.FromPactFile(new FileInfo("/path/to/pact.json"))

.withLogLevel(LogLevel.Debug)

.withLogLevel(LogLevel.Info)

.withLogLevel(LogLevel.Warn) // this one wins

.Verify();

I think that’s OK though. It would be overkill to attempt to make it compile-time impossible to do that, and the end result API

would be much worse because each of those options is also allowed to be omitted entirely. The important thing is that this

never creates an invalid state, and you always have to go through each required state to get to the final Verify call.

-

The final point isn’t really relevant to this article as it demonstrates provider tests and there’s only one way to do those, but consumer tests conform to a version of the Pact Specification (of which there are multiple). The equivalent consumer tests implementation uses type states which follow on from defining which specification version to use, and then each intermediate state only offers the options that are valid in that specification version and current state. ↩︎