Service Evolution with Consumer Driven Contracts and Pact

In a microservices architecture with a suite of inter-dependent services, ensuring fast feedback when API changes cause incompatibility becomes a key problem. Any time that incompatible services are deployed to an environment you will have caused a preventable outage that should be detected as part of your usual Continuous Integration solution.

At dunnhumby, we use a squad based approach to application development which sees small ‘vertical’ teams form with team members representing all of the ‘horizontals’, such as API, UI and QA. Each squad has its own backlog and priorities, but all must come together to deliver a single product to a single deadline.

Any organization that designs a system (defined broadly) will produce a design whose structure is a copy of the organization’s communication structure. - Conway’s Law

Owing to Conway’s Law we’ve naturally adopted a microservices development approach in our API design. Different squads are responsible for developing different microservices which represent their key business areas, such as pricing rules or competitor analysis. Each must be able to evolve independently whilst still forming a cohesive product made of these interacting parts.

Provider Driven Contracts

The central tenet of ensuring that this goal is met is that the different services must somehow define and conform to a contract between each other so that interoperability is achieved. One approach to this is for each service to generate some kind of binary output (such as a NuGet package or jar file) which is generated from its public API and acts as a client. This is known as Provider Driven Contracts because the API provider details to consumers which endpoints are available and the ways in which they must be used.

The development process that naturally follows from this approach when using a squad-based organisational structure and a microservices architecture is as follows:

- Team A needs to add a new feature to Service A. This feature requires retrieving data from Service B, which is maintained by Team B, but the API is not currently available.

- Team A talks to Team B to specify what they want, they agree and the change goes on to Team B’s backlog.

- Team A wait… They can perform the work required in Service A to support their feature and could stub out the calls to Service B in order to continue development, but ultimately they must wait until Service B is ready before they can properly integrate and deploy their changes.

- At some point in the future, Team B delivers an updated binary client containing the new functionality and Team A can now integrate properly.

In a fast-moving development environment this can cause a number of issues.

Firstly, any time that a team must wait for another team to deliver in to them is potentially time wasted. At the very least it introduces inefficiency if that team must create mocks/stubs that will eventually be thrown away. At worst, the time between the feature being needed and the feature becoming available might be long enough that the team has had to move on to a different story and now must back-track to integrate.

The next problem is one that developers in this scenario will be all too familiar with - the client binary arrives from

the other team and it doesn’t quite match what you thought had been agreed. Your stub has a field called product_id

whereas the client has productId. A few data types are different from your stub. The API arguments are slightly

different. You now must engage with the other team again and try to discuss what changes need to be made, agree them

again and then repeat the cycle. Hopefully you only need to do this once and hopefully the time delay is minimal, but

sometimes this isn’t the case.

These problems have been seen as necessary evils to achieve the major overall goal of ensuring API compatibility between services, and the best part of this approach is that this is absolutely guaranteed for the consumer.

However there are still additional, albeit more minor, problems for the provider in this scenario. By providing a client binary out to the world the provider has no way of knowing how the APIs are being used, or even if they are at all, until the API is deployed to a working representative environment. This makes evolving the API challenging because it’s unclear whether any particular API can be modified or even deleted entirely.

The provider also has no way of verifying that any changes don’t introduce problems until after the client has already been delivered to the wild. The provider squad must produce a new version, submit it to the package management repository, wait for clients to upgrade and then receive any feedback if any problems are introduced. Again, this introduces inefficiency due to the very long feedback loop.

Consumer Driven Contracts

Consumer Driven Contracts attempts to solve the same overall goal - ensuring service interoperability - by flipping the change control responsibility on its head. Each consumer of an API declares the specific contract that it needs from the provider and the provider’s job is to make sure that it meets the aggregation of all of the contracts from all of the consumers. Each consumer need only define the sub-set of functionality that they require following the Robustness Principle:

Be conservative in what you send, be liberal in what you accept

Using a framework such as Pact, these consumer contracts can be written as executable specifications that are run as part of the CI job of the consumer and the provider. Pact files are “contract by example” specifications which contain all of the required interactions (requests and responses) that the consumer requires of the provider. This allows a test-driven approach to API evolution backed by Continuous Integration to ensure that everything still works as expected even when unrelated changes are introduced.

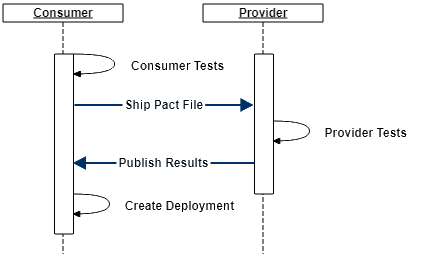

Our CI pipeline is as follows:

Every time a change is made to a consumer, the Pact specification is generated and shipped over to the provider. The provider then re-runs the verification test which executes each of the Pacts against the latest version of the provider. If the provider no longer meets one or more the specifications, the build will fail and the CI pipeline will stop. This ensures that these components are not deployed to an environment because we already know that they are incompatible. If the Pact specification is verified successfully then the changed Consumer component can continue to be deployed.

This approach solves the major problems of the binary client technique because the development process changes with it:

- Team A and Team B meet as before and agree the changes to be made to Service B.

- Team A write some new consumer tests in Service A which document the agreed changes.

- When these new tests are executed in CI, the build for Service B will turn red because the needs of Consumer A are not

met.

- In practice, our CI is set up so that if both consumer and provider repositories are using the same branch name, the branch build actually goes red. This ensures that master always stays green.

- Teams A and B continue working until the build is green again, at which point the two services are definitely compatible so the changes can be merged and deployed.

This test-driven approach prevents the problems introduced by the provider-driven approach because the feedback loop is much tighter. Every commit is checked to ensure that it still meets the executable specifications so problems are found immediately rather than after the clients have already been upgraded and/or deployed to an environment.

For the consumer, this means that they receive the required guarantees about compatibility upfront without having to wait until the functionality is available.

API evolution is also much easier because the consumers of an API are explicitly defined. If the team responsible for an API want to modify or delete it then they will get immediate feedback as to what problems that would introduce, if any, by simply performing the changes and running the tests. If the changes introduce no failing tests then they needn’t coordinate with any other team and can freely commit them. If the changes do introduce failing tests then the team can either decide to abandon the change or they will have a clear list of which consumers would need to change. This provides the starting point for a discussion with the other teams responsible. Pact also provides the Pact Broker which will document and visualise all of the interactions so you can tell how each provider is called and by whom.

This development process fosters an attitude whereby other teams that consume your APIs are seen as your customers, who are empowered to define the changes that they need instead of receiving the changes that you think they need. Inefficiency is greatly reduced owing to immediate feedback which boosts overall developer productivity.

Example

A Consumer defines pact interactions within unit tests which run against a mock server provided by Pact. This server will automatically respond to any registered request with the registered response so that you can test that your client classes make the appropriate requests and successfully deserialise the results.

For example:

public class ConsumerClient()

{

public ConsumerClient(string baseUrl)

{

// ...create a HttpClient...

}

public Task<Product> GetProductAsync(int productId)

{

// ...call the API using HttpClient...

};

}

public class ConsumerTests : IDisposable

{

private readonly IPactBuilder builder;

private readonly IMockProviderService provider;

public ConsumerTests()

{

var builder = new PactBuilder(new PactConfig { SpecificationVersion = "2.0.0" });

builder.ServiceConsumer("Consumer").HasPactWith("Provider");

// start the mock provider on port 8080

var provider = builder.ProviderService(8080);

}

public void Dispose()

{

// write the pact file to disk

builder.Build();

}

[Fact]

public async Task GetProducts_SuccessfulRequest_ReturnsProducts()

{

// arrange the interaction

provider.Given("some products exist")

.UponReceiving("a request for product by id")

.With(new ProviderServiceRequest

{

Method = HttpVerb.Get,

Path = "/api/products/123",

Headers = new Dictionary<string, object>

{

{ "Accept", "application/json" }

}

})

.WillRespondWith(new ProviderServiceResponse

{

Status = 200,

Headers = new Dictionary<string, object>

{

{ "Content-Type", "application/json; charset=utf-8" }

},

Body = new

{

id = 123,

name = "Peanut Butter",

price = 1.23

}

});

// act to ensure your defined class calls the provider properly

var client = new ConsumerClient("http://localhost:8080");

await client.GetProductAsync(123);

// assert that the API was called properly

provider.VerifyInteractions();

}

}

The result of running this test is a pact file named consumer-provider.json which then must be made available to the

provider CI task (we use an artifact dependency in TeamCity). The provider tests then start your API and instruct the

pact verifier to replay all requests within the file and verify that the real responses match the expected ones:

public class ProviderTests

{

[Fact]

public void ProviderSatisfiesPactWithConsumer()

{

// start your API

IWebHost host = new WebHostBuilder().UseStartup<Startup>() // from your regular ASP.Net Core Startup.cs file

.UseKestrel()

.UseUrls("http://localhost:5000")

.Build();

host.Start();

// run the interactions from the pact file and verify the results

verifier.ServiceProvider("Provider", "http://localhost:5000")

.HonoursPactWith("Consumer")

.PactUri("path/to/consumer-provider.json")

.Verify();

}

}

Conclusion

Adding Consumer Driven Contract testing with pact to our CI/CD pipeline ensures that we get fast feedback whenever incompatibilities are introduced into our APIs and eases the process of API evolution. The ability to tell prior to deployment whether our APIs can communicate is invaluable in ensuring new releases of our software don’t bring down an environment and impact our customers. The process fits in with our organisational structure and fosters a collaborative approach to development across different teams which improves development efficiency for all. Overall, introducing this pattern has been a great success for us.